In the dark hours of the morning, the entire town of quiet, little Emporia, Kansas transforms into a hubbub of cyclists from around the World. The announcer blasts over the loudspeaker wishing all of the riders a warm welcome to the day that they have been dreaming of and training for endlessly.

Unbound isn’t a race that you just “do.” It’s a beast that should be respected. It requires intricate preparations that surely preoccupy the hearts and minds of the riders long before they ever step foot into Emporia.

As an athlete and a coach, I’ve had a unique perspective into the event. I’ve coached amateurs and professionals alike toward successful finishes at Unbound. I, myself, with the help of my coach, tackled Unbound for the first time ever this year. With the deepest, most competitive, and most international field we’ve ever seen at Unbound we knew this year was going to be a doozy, but I don’t think anyone would have anticipated a 9-up sprint finish rolling into Commercial St after a record-breaking day of 10 hours and 26 minutes.

Here's some insights into what it takes to arrive at the start line, contend in the pack, and survive all the way to that drag race to the line in the professional women’s race.

Data Captured By: COROS DURA

Analysis Software: COROS Training Hub

Preparation:

Photos by Wil Matthews (@photowil)

Unbound requires months of training. In fact, as a coach, I recommend a minimum of 6 months of training in order to line up for the event. Competing at the pointy end of the field, is a different animal, entirely.

Most of the athletes in the front pack (and many not) race full time as their job which means the only limit to our training is what our bodies can handle. Since the start of 2024 until Unbound I averaged 20-hour training weeks, with weeks as high as 30 hours and of course some lower to help facilitate recovery. In addition to steady volume, it’s important to also have a couple of long “dress rehearsal” type of rides in which you can practice your race day nutrition and equipment. I did an 8-hour ride and a 12-hour ride as my longest efforts before Unbound.

This all might seem fairly cut and dry but the magic is what’s happening during those rides. Hours of intervals of varying intensities are the meat of my training. Another not-so-secret ingredient to success is the years of training most of us have under our belts.

First 20 Miles

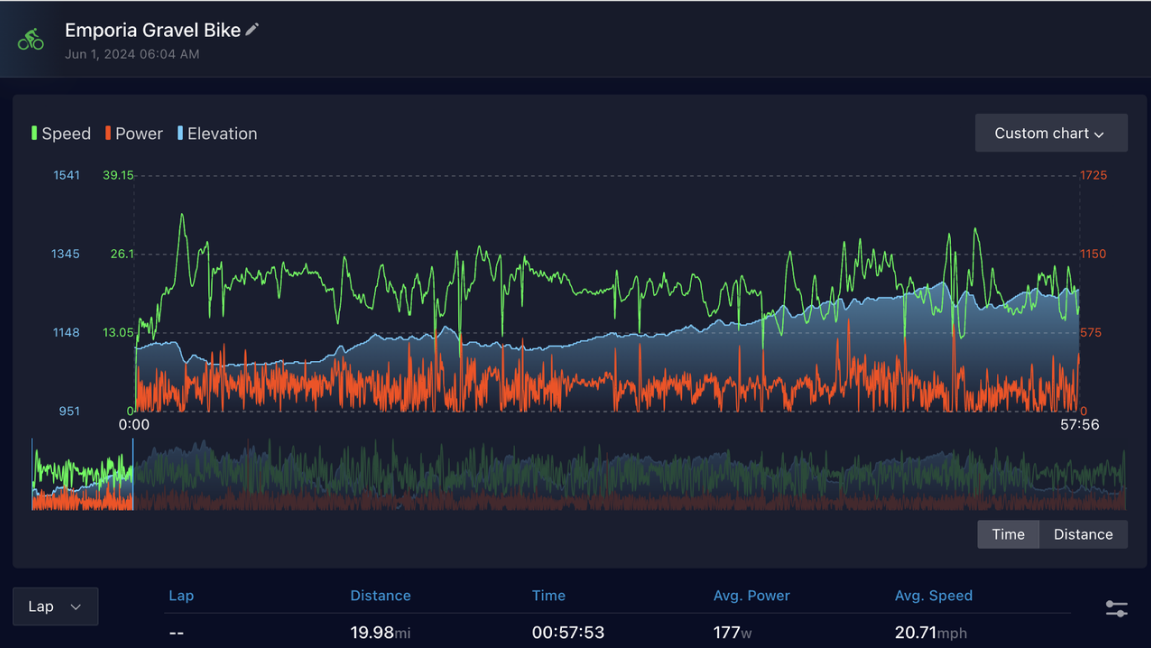

First 20 Miles of Unbound 200: Lead Women's Pack

The first 20 miles of the race are a balancing act. The overall goal of this time is to use as little energy as possible. Stay out of the wind and off of the front. The race cannot and will not be won in the first 20 miles, but it can be lost. That said, you must balance that with the fact that you must stay in the group. You cannot allow a split to happen with heavy hitters going off the front. Equally, you cannot allow yourself to continually yo-yo off of the back of the group causing you to use matches to catch back on.

The majority of the first 20 miles were spent around 3.7 watts per kilogram with several 1-2 minute spikes up and over 5.8 watts per kilogram. Additionally, I used my COROS DURA headunit mapping feature during this time along with mileage and the knowledge of the course to help notify me when important features were approaching to help inform where I should be in the pack.

The Final Selection:

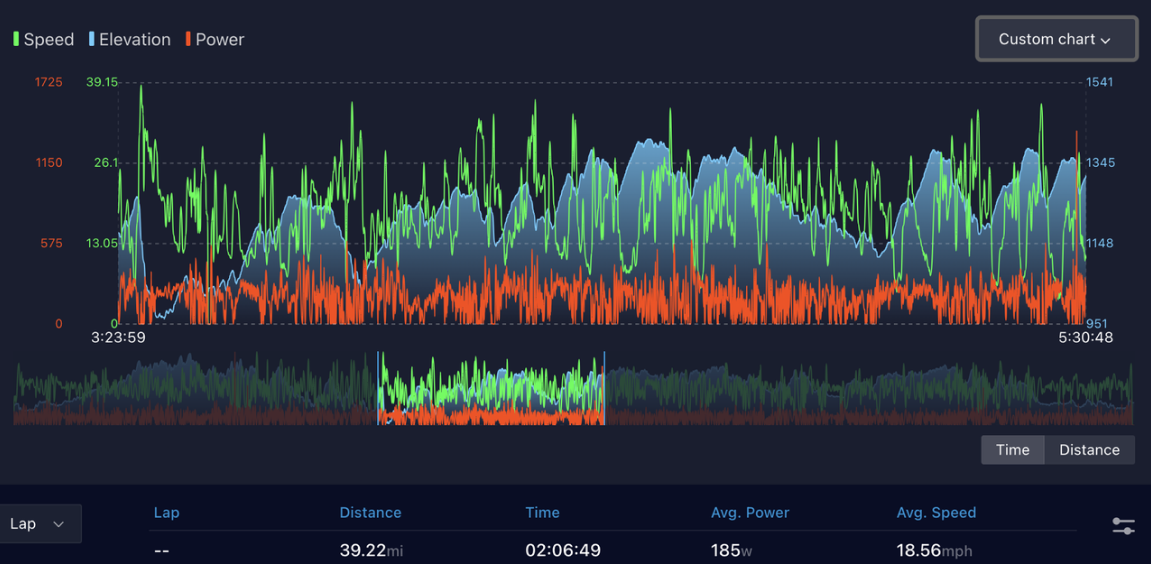

Mile 40 Section of Unbound 200

There were several “selective” moments of course. The first of which happened around mile 40 and split the group of 60 riders in half. Along with challenging terrain, rocks, and ruts, this will cost a rider around 15 minutes at 4.6 watts per kilogram according to COROS.

The next split appears to be less obvious in the numbers because the course became much more sporadic and our group began to work together as the numbers of people in the group dwindled. Your efforts were greatly impacted by where you sat in the pack and how steep the climb was.

Mile 70-110: Unbound 200

From Aid Station 1 at mile 70 to mile 110 (after the infamously rough and rocky Little Egypt) to survive in our group, according to the COROS app, you would need to sustain 3.8 watts per kilo while also enduring short lived efforts going as high as 8 watts per kilogram. At mile 100, our group had whittled to 11 riders.

Survival:

Steady riding within the women's lead pack

For the next 90 miles, the pace did soften to a normalized power around 3.5 watts per kilogram. This is largely in part to the fact that our group began to work together. The selection was made and for a short time, our group would be allies, securing our position in the front of the race. We aimed to take short pulls up front with a fast and aggressive pace and rotate off quickly spinning as easier intensities in the back of the group until it was your turn to pull again.

As we neared the finish, the pace became very hot and cold. Short and steep climbs required efforts over 6 watts per kilogram but in a game of cat and mouse our group often lulled in the closing miles to try to push people who had been hiding from the wind all day to finally take their turn at the front. We shed two people during the final short and steep climbing efforts. The group was now 9.

The Sprint:

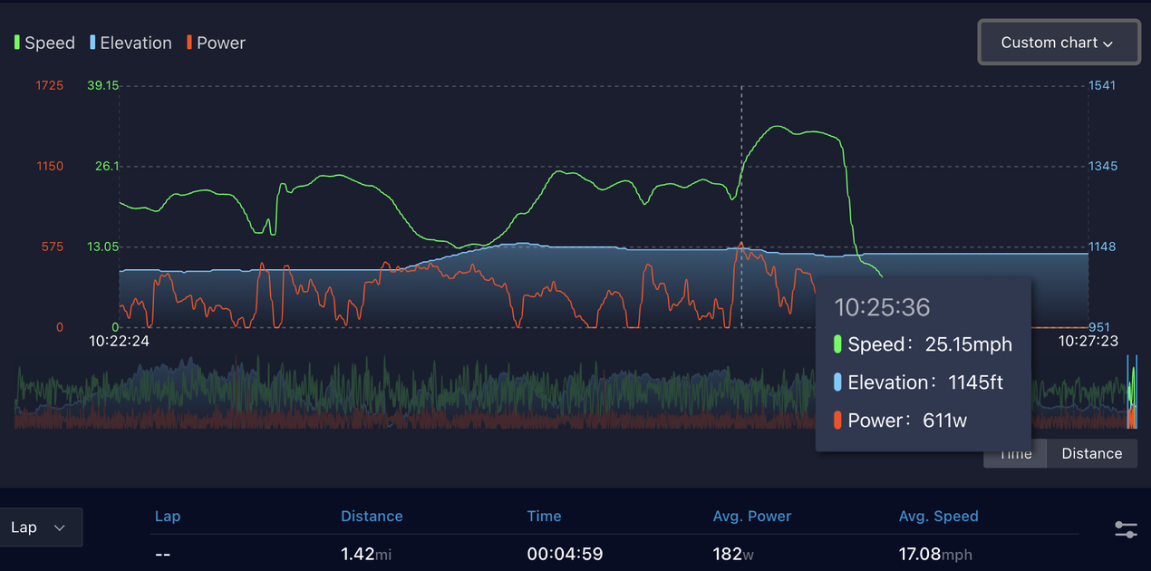

In the closing miles, it became obvious that a sprint finish was in the cards. I knew there was one final climb only a half of a mile from the finish. I hoped that if I attacked there I could have whittled down the group one more time before finishing with an all-out sprint to the line. I hoped that if I went there, I might cause the others to give up. After 10.5 hours in the saddle, any effort feels like a hard one.

Attack and sprint at Unbound 200

I jumped and held 7.3 watts per kilogram for nearly a minute. It wasn’t enough. With the high speeds, others were still able to draft and hold my wheel. The competition was fierce. No one would give up. As my legs screamed from that effort, and my vision became blurry from the intensity, I attempted to stay on the gas and maintain position going into the final sprint, which after nearly 10.5 hours in the saddle, peaked at just below 10 watts per kilogram.

My legs hurt. My lungs hurt. Every muscle in my body hurt. But my heart hurt too. After 10.5 hours in the saddle, I finished 8th, just 2 seconds away from winning the biggest gravel race in the world. I’m elated with my effort and the overwhelming emotion is joy, but the competitor in me also feels the pain of being so close, yet so far. I suppose that gives me all that more reason to come back next year. And now, I know what it takes.

/fit-in/0x9/coros-v2/images/common/logo_black.png)

/fit-in/252x0/coros-web-faq/upload/images/abf0c9f67f001357d23f9b53ecf91a21.png)